Discovering hidden art. Courtesy of Diana A.Tay

Why did you decide to go into art conservation?

I did my degree in fine arts right after high school. From what I can remember, there was an emphasis on having strong concepts, big ideas, meaning embodied in materials, material exploration and moving away from traditional media. These were very intimidating at that time and all I wanted to do was just draw and paint horses, spend time on very detailed sketches, improving my technical skills – you can imagine – for an examinable subject, I did not do well at all!

In retrospect, my ignorance at 17 limited my understanding of the world, of myself and my exploration in art – I didn’t have a great story to tell. Before you read on thinking that my art school story is going to have a horrendous or traumatic ending, it was actually a big part of how I discovered conservation. As part of the degree, I had to write a dissertation about an issue in contemporary art. That was when I was introduced to the works of Feliz Gonzales-Torres and Janine Antoni which got me thinking about these works in museum spaces and the idea of ephemerality.

I was absolutely clueless about conservation so it was not something I could make an informed decision about going into. But I started thinking about what I would do if I were a conservator and what they say about thoughts having frequencies may be true because, right after graduation, there was a job opening for an assistant paintings conservator for the National Collection – and that was how conservation found me.

What is conservation and what kinds of artwork does it deal with?

Conservation is such a broad discipline and is increasingly multi-disciplinary. It can involve art history, cultural and heritage studies, material studies, science – the list goes on. Recently, I worked together with an artist, curator, collection manager, collector and a scientist – all at the same time – to come up with the best conservation approach. In short, to conserve is to collaborate and it can never exist on its own.

As a paintings conservator, my job ranges from documenting artworks, to performing interventive treatments, such as the cleaning of paintings, to the consolidation of fragile paint, to taking preventative conservatory measures, such as monitoring pests and the environment. And increasingly for contemporary artworks, having interviews with artists! Designing the best approach for conservation begins with understanding the artist’s intent/sanction and then assessing and weighing up the risks and significance of the treatment. Conservation is decision-making at its best.

We deal with culture and heritage. So, that is pretty much anything that means something to someone or a community. It can range from pot shards, family photographs, paintings from the 18th century, performance art relics, installation art, digital and even interactive art.

Conservation of contemporary art. Courtesy of Diana A.Tay

What is the difference between conservation and restoration? How do they work together?

The field of conservation is pluralistic and, in contemporary times, conservators’ professional skills may include scientific knowledge, and engagement with the wider community, amongst many others, as part of the process of preservation. I suppose that ‘restoration’ can be seen as an act to return an object to its presumed original appearance/function. With that said, conservation can involve elements of restoration, but it is not always necessary.

In the discipline, these two words may, at times, exist in a state of tension with one another and it can become problematic when one tries to pigeon-hole what ‘conservation’ or ‘restoration’ is. It might be interesting for you to discover that to bridge this, the term ‘conservator-restorer’ was adopted by the International Council of Museums.

My personal take on it is that conservators and restorers are individuals. There are principles of ethics to adopt in the conservation profession, such as minimal intervention, reversibility, and respecting the original medium. And definitely, our treatments do have consequences – some actions may be irreversible (for instance, the removal of dust or varnish off a painting), and the materials or techniques chosen for treatments may vary between individuals and may depend on accessibility. Because conservation is essentially decision-making, I cannot say all conservators would arrive at the same decision!

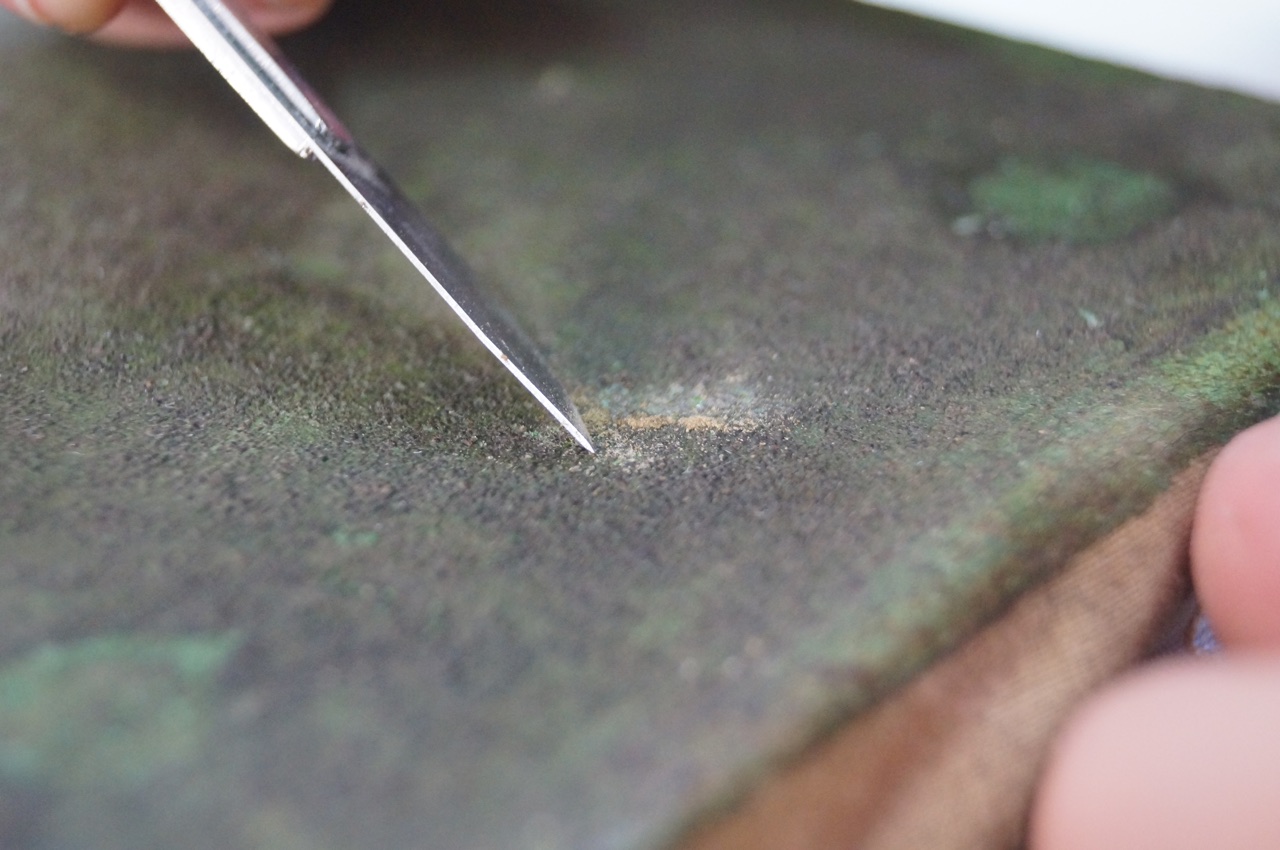

Taking sample from a painting. Courtesy of Diana A.Tay

Should you think about how to preserve your piece of art right after you create it or purchase it?

This is pretty much an occupational hazard for myself and my friends! I started buying artwork a few years ago and the first thing that pops into my mind each time is “Can I take care of this?”. I am very aware of how dangerous this can be for artists though. Especially for artists exploring experimental materials and are pressured to answer questions about change from their galleries/collectors. And I say dangerous because it can get in the way of creativity and may limit their material choices if the forefront of their mind is concerned with “How can I make my work last?”. That said, it is good to think about it though. If you are facing material incompatibilities or you’re open to exploring materials that have a longer lifespan, you can speak with a conservator! The degradation of materials is almost unavoidable; the rate of degradation for some materials is faster than others. Perhaps, not all artists want their works to last forever.

Instead of asking ‘How can I make my work last?’, you could ask yourself, ‘How can I best take care of my work?’. Preservation starts in the little things – from the way it is stored, keeping a healthy air circulation, minimising the risk of insect attacks, light damage, human damage – you’d be surprised by the frequency of damage that occurs when people trip or fall into their works of art!

Working with heavy tools, too. Courtesy of Diana A. Tay

Do you think it is possible to preserve a piece of art forever, considering the technology and knowledge we have these days?

Despite the advancement of technology and the increase in our knowledge — time is not something we can ever escape. Just as we can’t stop our skin from wrinkling, we can’t preserve a piece of art forever. I’m not sure how long forever is — but in the duration of our lifetime, there are ways to slow the degradation down.

How has conservation and its techniques evolved in the past century?

To put this into context, the television was only invented in 1925! In the past century, a lot has changed in the world, and that includes what has made art, art. Conservation is an ever-growing and changing field, and there is a strong need and demand to remain relevant. For instance, conservation now includes the conservation/preservation of digital art. This is an entirely new skill set and the terrain goes beyond the ‘restoration’ of a physical object. There has also been more critical discourse that has challenged and critiqued the approaches to conservation. The advancement of science has enabled us to understand material behaviour better, as well as changes to artist’s techniques, the improvement of cleaning techniques and there is still much more to learn! I think conservation has come a long way – from the doing to thinking, and importantly, re-thinking.

Microscopic image of paint. Courtesy of Diana A.Tay

Who are the famous or renowned specialists in your field?

Because it is such a specialised field but, at the same time, it can be so broad, this is a difficult question to answer! Some conservators dedicate their lives to becoming an expert in an artist’s practice, while some have focused on research regarding an art movement, geographical region, material type, or even cleaning techniques! It’s hard to name names but a commonality I’ve observed amongst the specialists I’ve worked with is that they believe in what they do and are all really passionate about sharing their knowledge. Also, they can explain very complex things in very simple terms.

Where do you recommend to study to become an art conservator?

It depends what you’d like to focus on! For conservation, there are general specialisations – objects, paper, textiles, paintings, heritage sites, amongst many more. So it’s good to think about what you’d like to come in contact with, although I do emphasize that these categories are not meant to limit or restrict your practice! There are quite a few schools of conservation in America, Europe, and also in Asia, so a running a search through Google and speaking to the course coordinators is a good start to see if this is the field for you.

For me, I’ve undertaken my studies with the University of Melbourne because they’ve got research strengths in the conservation of cultural materials in the Asia Pacific region, which is relevant to my practice. I’ve also chosen to specialize in the conservation of paintings but, you know, these categories are not limiting. It all depends on what interests you, and your willingness to learn.